By Matt Klampert

These days, the YUKIGUNI region of Japan is well known as a mecca of winter sports, such as skiing and snowboarding. However, the history of skiing in Japan only goes back to the early 20th century. Prior to this, the former “Echigo” was famed for its long history of producing quality textiles. Textiles are not the hard square tiles that might cover your floor or bathroom, instead they are defined as “a fiber, filament, or yarn used in making cloth.” A special variety of textile, called “Echigo Jofu,” is made exclusively in Niigata.

Echigo Jofu- the famed fabrics of Snow Country

What is called Echigo Jofu is not actually a cloth like silk, but instead ramie, which is sometimes called karamushi in Japanese. It is a common plant in the nettle family native to this area that is similar to flax. Garments such as kimono which are made from Echigo Jofu are highly prized for their beauty as well as durability. In the past, this ramie textile was referred to in English as “Echigo Crepe,” however what we call crepe cloth in the west is typically silk or wool garments which were used as mourning attire. What they do have in common is their use of crimped, or twisted fabric.

Echigo Jofu through the ages

The history of Echigo Jofu is a long and interesting one. One of the first recorded mentions of it goes back almost one thousand years to 1192, when it was sometimes given to esteemed courtiers as a personal gift from the Japanese emperor himself. Merchants would travel from far and wide to purchase the prized textiles, and one of the primary markets for Echigo Jofu was located in Shiozawa, which is now a part of Minamiuonuma City.

Back then, there were a few different markets to support the large amount of textile trading, and in addition, each village in YUKIGUNI was known for their own trademark variety of Echigo Jofu. For example, a beautiful white Echigo Jofu was produced in the areas of Horinouchi and Koide in what is now Uonuma City, while Tokamachi and Muikamachi were known for different shades of blue textiles. Shiozawa meanwhile, has a tradition of producing a specific patterned textile called kasuri, which is still produced to this day.

The skilled textile-makers of Snow Country

Unfortunately, outside of Shiozawa, Muikamachi, and nearby Ojiya city, most regional varieties of Echigo Jofu are no longer produced. Instead, the type and pattern of textile varies according to each company. There are still some local makers of Echigo Jofu for whom knowledge and skill of this craft has been passed down from generation to generation.

Weaving these textiles originally began as a pastime for women in the Snow Country while snowed-in during harsh winters. This allowed the families, most of whom were poor farmers, to supplement their income. Because of this, women in YUKIGUNI who were considered the best weavers were often valuable marriage partners. However, despite Echigo Jofu being recognized among Japanese nobility as a valuable commodity, these women remained in poor circumstances and unknown outside of their small communities.

A timeline of making Echigo Jofu

Even though the making of these textiles are often thought of as being synonymous with winter, it is in actuality a much more time-consuming activity, the preparation of which takes much of the year. The process starts the previous spring, where the fields for growing ramie are burned off to revitalize the soil, and then the ramie is grown and cut in summer. The spinning of the ramie begins in November and lasts through the winter.

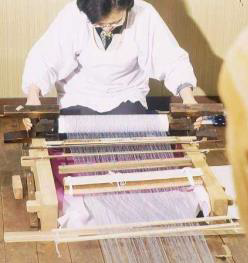

Ramie is made into extremely thin threads for garment making. In order to strengthen the thread, it is wound around a bamboo tube multiple times and twisted in a process called chijimi. Then, a special glue is applied to it, and the threads are stretched by bamboo rollers. The thread is woven by a special machine called an izari, and dye and patterns are applied to the cloth. All told, weaving and producing Echigo Jofu is much more time and labor intensive than the production of normal cloth. The ramie needs to be kept at a high humidity, and for that reason people used to bring snow inside their homes while weaving.

Before the industrialization of textile-making, author Bokushi Suzuki estimated that to weave a 27-foot length of Echigo Jofu cloth required 24,484 precise hand and foot movements. This was painfully precise and exacting work: a famous story tells of a young woman who sought to establish herself as a weaver and made an entire ramie garment herself, but when a small stain was unfortunately found in the finished product, she went completely mad.

Snow-bleaching- Yukisarashi

Beginning in February, the cloth is brought outside into the snow and undergoes a bleaching process known as yukisarashi. This is a natural bleaching process done without harmful chemicals. The yukisarashi occurs from February to March, when the snow begins to melt in a place where there is a flat plain and plenty of sunlight. The cloth is kept here from between a week to 10 days, after which time the fiber gets its trademark snow white color. Because lye or other chemicals are not used, the fabric stays strong, and the color intensity lasts longer than other fabric, and is less likely to yellow as it ages. There is also a process called satogaeri, where old jofu cloth is brought back to the snowy fields here, and once again undergoes the snow-bleaching process. This revives the cloth and gives it its signature vibrant color once again.

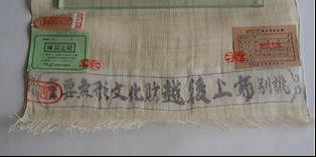

In the past, people did not know exactly why snow bleaching worked so well, and attributed it to the effects of yin and yang. However, we know now that the reflection of sunlight off the snow actually causes a low-pressure current of hot air approximately 2-3 meters above the snow. In this situation, the hydrogen and oxygen in the water vapor separates and creates ozone. The ozone, reacting with heat from the sun, naturally bleaches the ramie fibers. After 10 days in the snow, the material is finished at a machine shop with warm water, and is then smoothed out and inspected according to such criteria as the thread length and width, and the pattern and dye quality. If it passes, it is then considered to be quality Echigo Jofu.

Come and see this prized cultural heritage of YUKIGUNI!

Echigo Jofu was finally registered as UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2009. Most years, people who visit Shiozawa and Muikamachi in February and March can visit the snow fields and see the snow-bleaching firsthand. Local Echigo Jofu cloth can also be purchased online HERE. Also, click HERE for tour information to see the making of Echigo Jofu and yukisarashi on your next YUKIGUNI trip.

-1024x626-2.jpg)