By Matt Klampert

In the past, before telephones, television, and the internet paved the way to our current “information age,” there was a time when the YUKIGUNI region was not well-known even among Japanese people. Especially in the time before winter sports took hold in Niigata and Nagano, the Snow Country area was mostly overlooked, and its people and culture ignored. The idea of “Snow Country” was popularized and romanticized by the Nobel prize-winning author Yasunari Kawabata, but Kawabata himself was not from this area, and there was much about it that he didn’t know. To learn more about Snow Country Kawabata is known to have read the works of another writer, a man named Bokushi Suzuki, whose influence in Snow Country can still be felt today.

A little bit about Bokushi Suzuki

Bokushi Suzuki was born in 1770 in Shiozawa, now a part of Minamiuonuma City, to a prosperous merchant family. Bokushi’s father was a successful cloth merchant as well as a poet of some renown. Despite his wealth and connections, however, Bokushi’s station in life was limited by the fact that he didn’t belong to the samurai class. As a teenager Bokushi moved from Niigata to Edo-now known as Tokyo- to sell Echigo Jofu cloth for his family. With the money he made, Bokushi opened up his own shop in the city.

Though nominally a businessman, Bokushi was equally interested in literature and art, and sought to ingratiate himself with the intelligentsia- famous poets, artists, and philosophers- from all over Japan. These friends would often exchange poetry, letters, and calligraphy with one another. This was a time when people would write at length in letters to one another, almost like a personal blog that you would send to all of your friends. Realizing how little-known his homeland was, Bokushi eventually had an idea to publish a book of tales to teach city folk about life in YUKIGUNI. This would become Bokushi’s life’s work.

Finally, after 40 years of work the book was published in 1837. Called “Snow Country Tales,” or Hokuetsu Seppu in Japanese, it became a huge success. Bokushi, who was in his sixties by this time, planned on writing another book, but suffered from ill health later in life, and passed away in 1842. Other works, including a book of haiku poems, were published posthumously. “Snow Country Tales” is still widely read in Japanese to this day, and has been translated to multiple languages, including English.

About the book

Bokushi’s book “Snow Country Tales,” rather than being definitively fiction or non-fiction, can be thought of as a collection of facts, tall tales, firsthand ethnographic studies, and other musings from the author. Unlike other writers before and since, Bokushi chose not to romanticize his homeland, and instead strove to portray it as realistically as possible. He felt that YUKIGUNI had been unfairly ignored, and that there were many aspects of the land and its people that was deserving of attention.

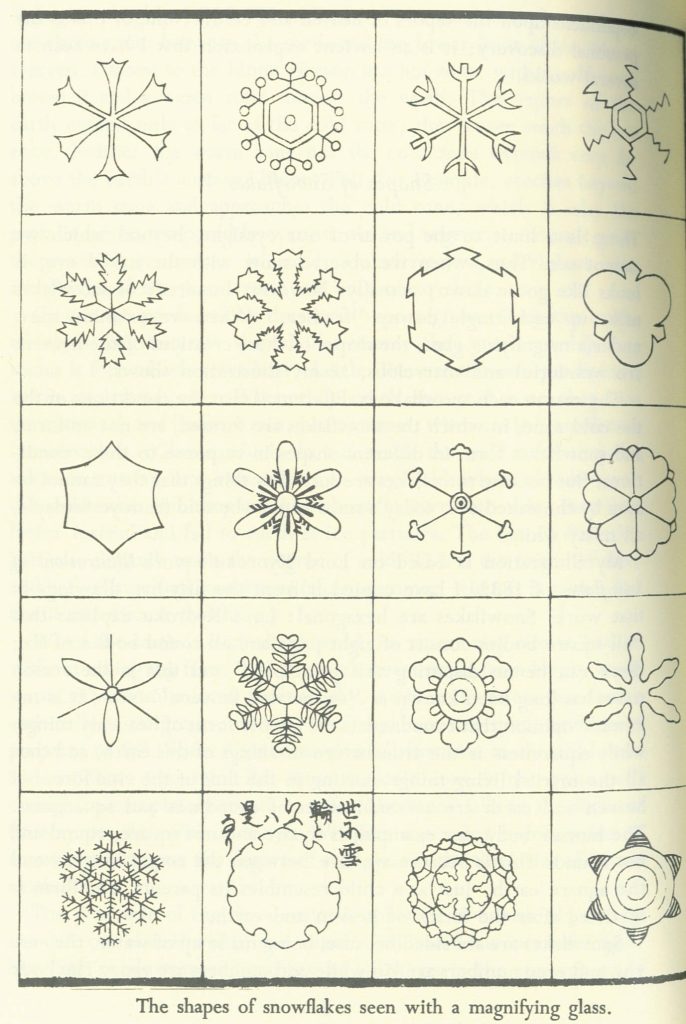

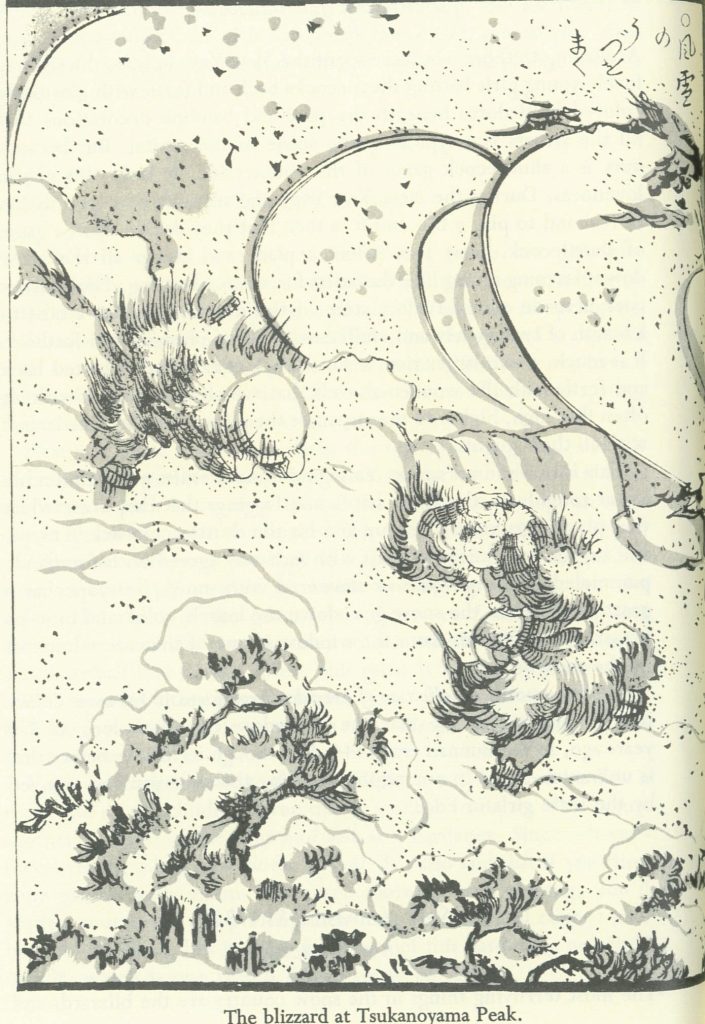

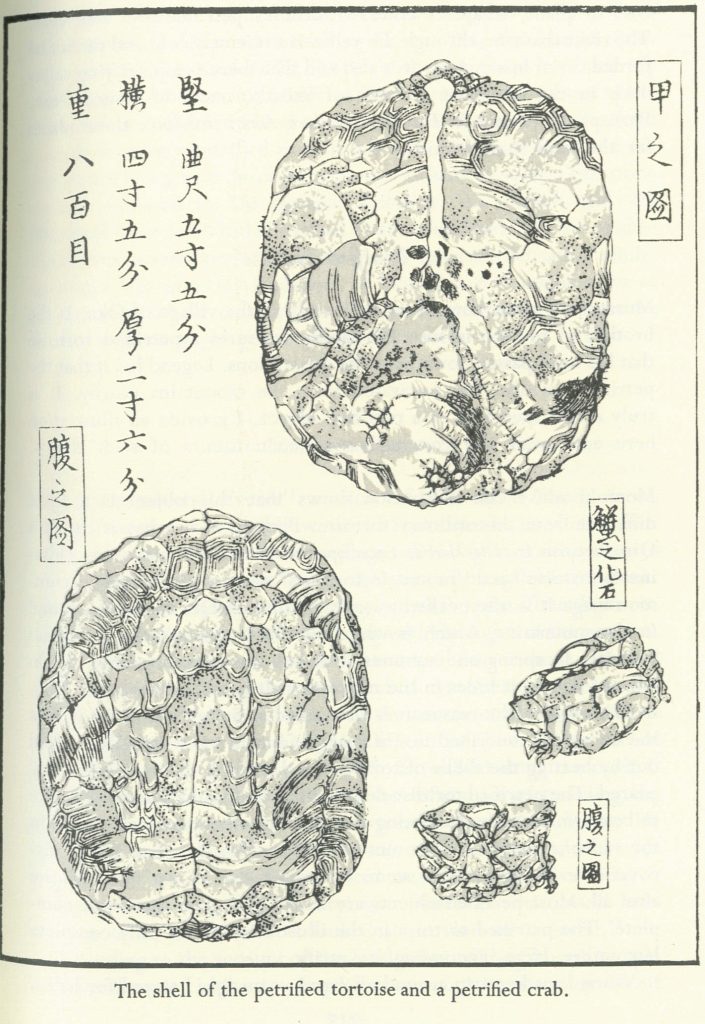

Another quality of Bokushi’s work is that it teaches us much about who Bokushi was as a person. We know how well-read Bokushi was due to his numerous allusions to Chinese classics, as well as works from his Japanese contemporaries. Bokushi, like many people of his day in Japan, was influenced by traditional Chinese beliefs such as the presence of yin and yang in the natural world. He also shared a belief in the sprit world, and presents ghost stories that were related to him as though they were factual. When speaking from his own experience though, Bokushi does often give valuable, and sometimes practical information, such as what to do when caught in a blizzard. The book includes illustrations of snowflakes, which were based on those that were taken with an early microscope, and were the first of their kind.

Life in the Snow Country

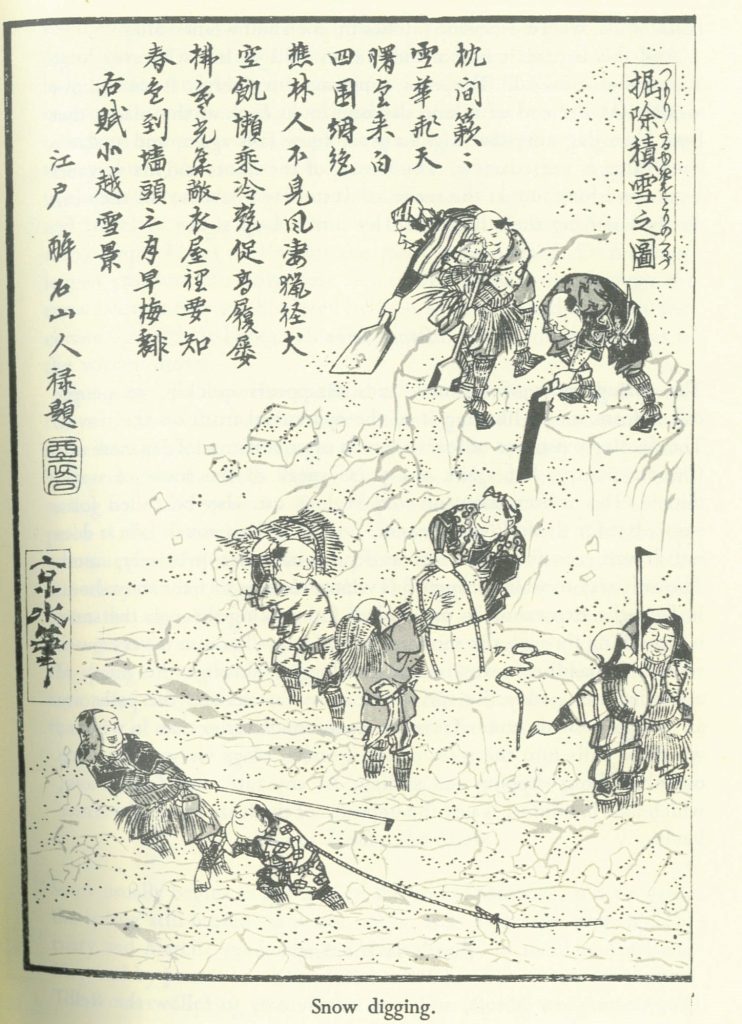

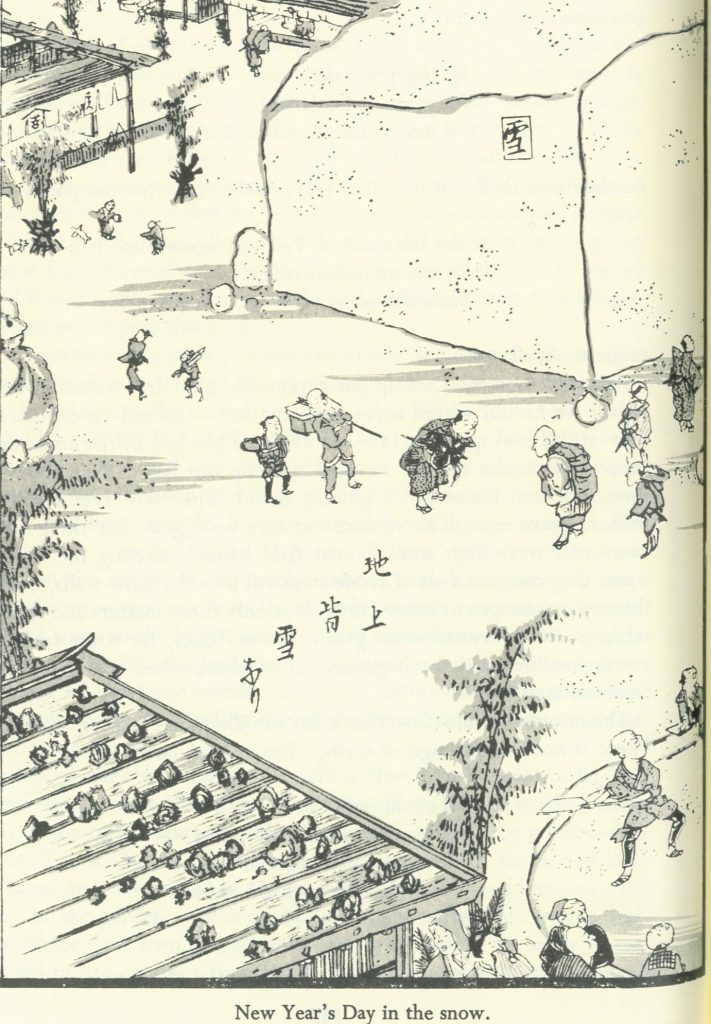

So, what’s there to write about in a book all about Snow Country? Well, how about snow? Though the idea of a snowy world was heavily romanticized at the time, Bokushi’s biggest contribution was to inform people about the real-life hardship that came with living in a region with such severe winters. Bokushi writes in detail about how the lives of snow country people largely revolved around snow. Especially back in the 18th and 19th century, when the technology didn’t yet exist for giant machines to come and remove swathes of heavy compacted snow, it would often remain on the ground well into summer. This in turn affected how farming here was done. However, snow also had its uses, like preserving food so that people could survive being snowed-in all winter.

Notable places in Snow Country

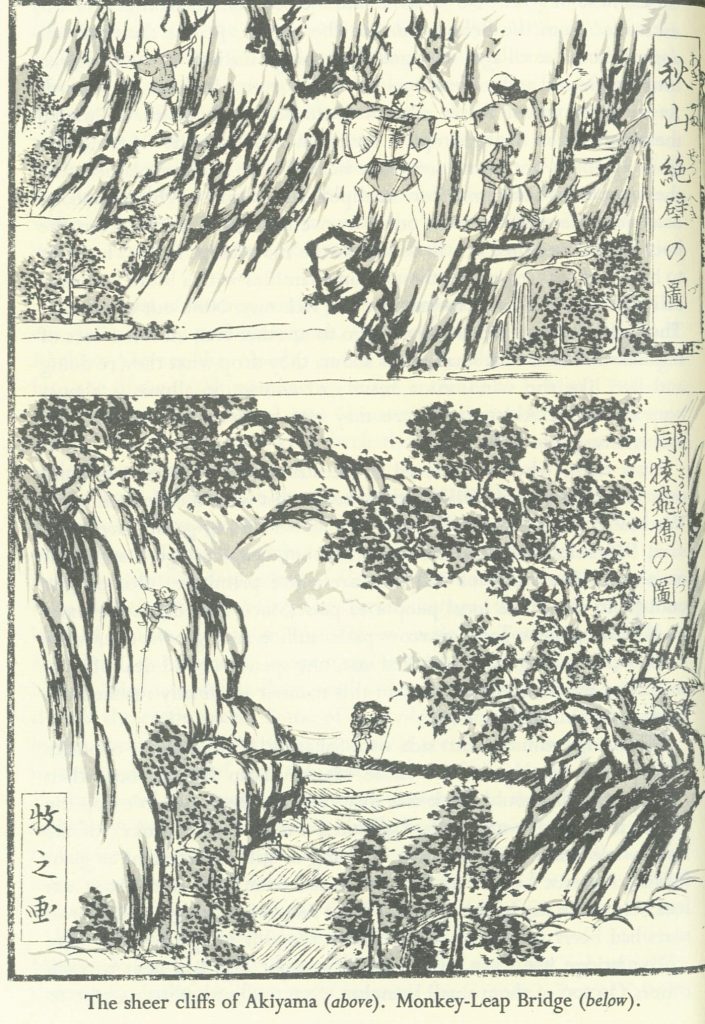

Though Snow Country Tales is not a comprehensive travel guide, there were certain areas in particular which Bokushi especially wanted to tell people about. One of them was Akiyama-go, a series of connected villages that is located between Niigata and Nagano prefectures in what is known today as the “Naeba Sanroku Geopark.” It was originally rumored that the descendants of the famous Heike clan of samurai resided in this remote area. Bokushi gives a detailed, firsthand account of encounters during his travels there to show how these people lived. Bokushi was so fascinated by Akiyama-go that he later wrote another whole book about his experiences in this land, but it was unfortunately not published during his lifetime. Bokushi also talks about the beautiful nature surrounding YUKIGUNI, such as Mt. Naeba. Elsewhere, Bokushi mentions a famous temple, Untoan, in Minamiuonuma. This 1,300 year-old temple is known for having 70,000 stones buried under the ground, each of which contains an inscription of the lotus sutra.

The spiritual life of Snow Country people

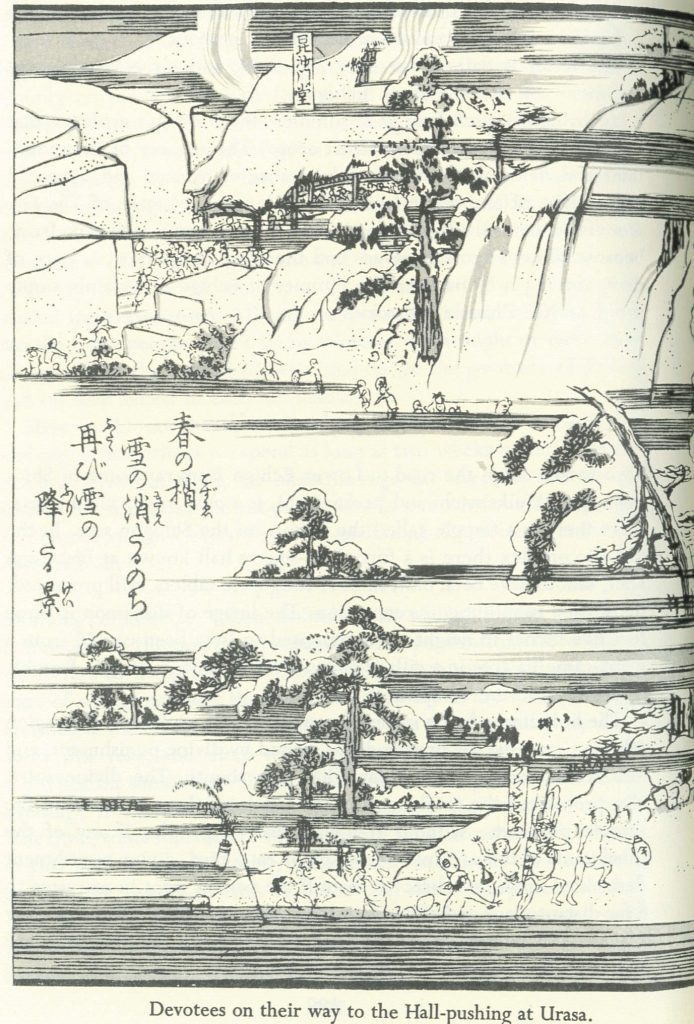

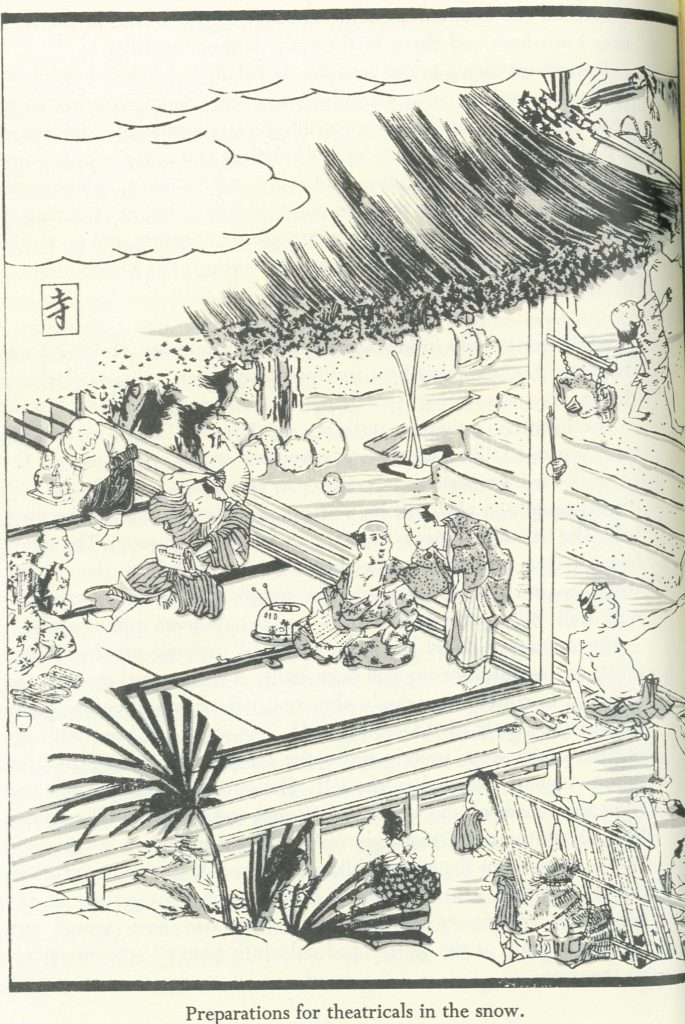

Having grown up in YUKIGUNI, Bokushi was well acquainted with the spiritual lives and traditions of the people here. In those days the people of Snow Country followed “Pure Land Buddhism,” which is typified by veneration of the Amida Buddha and the chanting of the lotus sutra. YUKIGUKI spirituality also entailed a celebration of ascetic practices, which included enduring extreme cold as a way to purify oneself. People here observed special ceremonies for certain times of the year, such as the Echigo Urasa Naked Festival, where people would pack into the Fukoji temple in Minamiuonuma while scantily clad to harness the power of the deity Bishamonten. This thousand year-old festival remains mostly unchanged to this day; you can read about it and other festivals around YUKGUNI HERE.

Yukiguni’s famed Echigo Jofu Cloth

Coming from a family of cloth merchants, Bokushi was very knowledgeable about YUKIGUNI’s famous Echigo Jofu cloth. In “Snow Country Tales,” he gives very in-depth accounts about everything regarding the making of such cloth, where it was sold, and its significance to YUKIGUNI culture. In particular, the weaving of cloth was primarily done by women, and as the production of Echigo Jofu became more lucrative, the women who were the most skilled became sought-after marriage partners. Bokushi also recounts the difference between different kinds of Echigo Jofu. Back in his time, every village wove differently colored and styled cloth. As many of these techniques and traditions have been lost to history, Bokushi’s accounts are invaluable. We have written more about Echigo Jofu, Yukisarashi, and its significance HERE.

The flora and fauna of Snow Country

Bokushi, in addition to his other talents, was a keen amateur naturalist who wrote much about YUKIGUNI’s animal and plant life. Most notably, Bokushi introduced the rest of Japan to yukimushi, many types of insects that only live in YUKIGUNI and nowhere else. Another popular subject was bears. Bokushi knew many traditional hunters, known as “Matagi,” from whom we learn how men of that day undertook the dangerous task of tracking and killing bears in the mountains.

In addition to creatures that do exist, “Snow Country Tales” records some of the mythological creatures said to have lived in this part of Japan. One in particular whose myth has endured is the yukiotoko, which is described as having had “long white hair” and being “taller than the average person.” Bokushi writes, “And, although its face did resemble that of an ape, it was not red, and its eyes were enormously big and shining.” Bokushi tells tales of people encountering yukiotoko, and being helped by them. Though we cannot tell you how or where to encounter a yukiotoko yourself, local sake brewery Aoki Shuzo has named one of their signature varieties of sake after the mythical beast, which you can read all about HERE.

Learn all about Snow Country Tales in Snow Country

In order to learn all about the world of “Snow Country Tales,” why not visit Bokushi Suzuki’s own museum? Located in his hometown of Shiozawa in Minamiuonuma, the Suzuki Bokushi Memorial Museum contains many artifacts from Bokushi’s personal collection, both as a literary light and in his capacity as a cloth merchant. As Bokushi was fastidious about keeping everything, there are all sorts of one-of-a-kind items on display, which include explanations in English. Also nearby is Bokushi-dori, the historic street that was renovated in an Edo-period style. It is the best way to experience the world as Bokushi knew it two hundred years ago.

Information for Travelers

Suzuki Bokushi Memorial Museum

Address: 1112-2 Shiozawa, Minamiuonuma City, Niigata Prefecture 949-6408

Hours: 9:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.

Cost: 500 yen per adult

Untoan Temple

Address: 660 Unto, Minamiuonuma City, Niigata Prefecture 949-6542

Hours: 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.

Cost: 300 yen per person

Mt. Naeba

Address: Mikuni, Yuzawa Town, Minamiuonuma District, Niigata Prefecture 949-6212

Hours: N/A

Cost: N/A

Akiyama-go

Address: Akiyamago, Tsunan Town, Naka Uonuma District, Niigata Prefecture

Hours: N/A

Cost: N/A

-1024x626-2.jpg)