Blessings of snow

One of the blessings of snow in the textile industry is the “snow bleaching” process, through which the people of YUKIGUNI bleach their yarns and fabrics. In addition, the pure soft water created by the penetration of snow water into the stratum creates a wonderful color effect when dyeing.

YUKIGUNI textiles loved by the aristocracy

Due to its high quality, hemp textiles from Echigo were used as gifts by aristocrats for a long time, and were even stored in the Imperial storehouse of Todaiji Temple.

In this article, I would like to introduce Echigo jofu which are also registered as intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO, Tokamachi Kasuri is a traditional Echigo linen weaving technique applied to silk weaving, Angin which Jomon period clothing, Tokamachi Yuzen of dyed kimono.

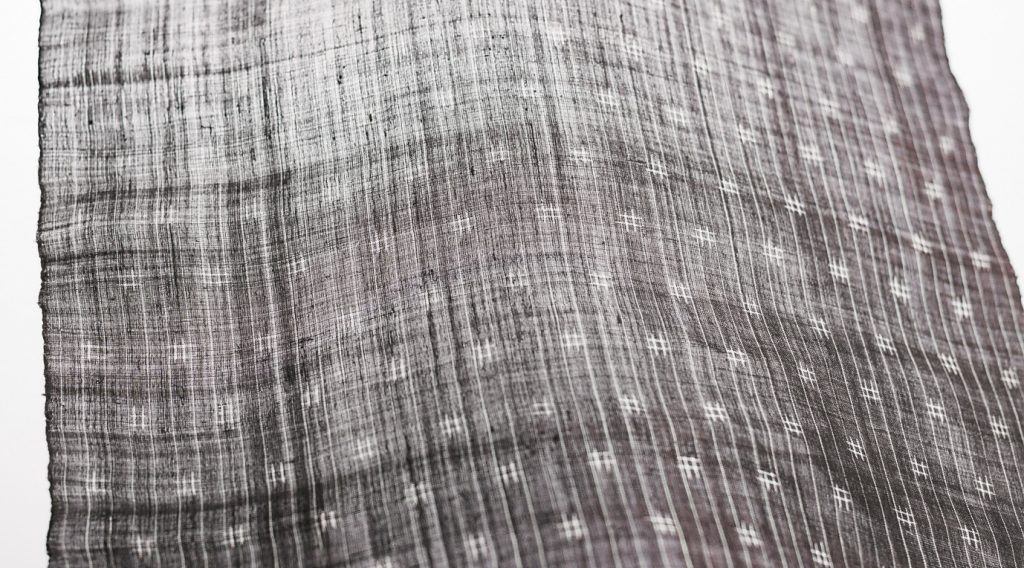

Echigo jofu

Echigo-jofu, which has been designated by Japan as an important intangible cultural asset, and designated by UNESCO and intangible cultural heritage, is produced by means of a manufacturing method which must comply with amazingly strict requirements.

First, threads handmade from the ramie plant must be used. Second, if a dye pattern is added, this must be hand-produced. Third, the fabric is produced on an izari loom. Fourth, when the fabric is being wrung, this must be done with hot water by hand and by treading on the fabric with one’s feet. Five, bleaching must be carried out by means of Yuki-sarashi (snow bleaching).

We spoke to Ms Akemi Takanami, a weaver who produces Echigo-jofu. The vertical thread is stretched across the loom, and the part of the thread to be woven is carefully dampened with a wet brush. “If you don’t do this, the thread might snap. This is because hand-produced linen threads snap particularly easily. In the YUKIGUNI, humidity is high, which is exactly why we can produce Echigo-jofu here.”

She adds that the finished products are Yuki-sarashi (snow-bleaching) in March, which is when you can start to feel the arrival of spring in the YUKIGUNI. The fabric is bleached by the ozone which emanates from the snow.

“Echigo-jofu is entirely handmade. In order to produce a tenth of one hectare of fabric, it takes two years.” Ms Takanami is also engaged in raising the next generation of weavers. “If we neglect the tradition of Echigo-jofu, it will definitely die out…”, she says with an expression which conveys her strong determination not to let this tradition die.

Climate suitable for woven textiles

The high humidity in YUKIGUNI prevents threads from snapping during spinning, twisting or weaving. In the past, people cut the ramie in autumn and then waited for the snow to fall to start weaving. Furthermore, this is a humid region which is rare in the whole of Japan: As it is located in a basin, there is only little wind, and the humidity is high during the entire year (79% on average). Moreover, the temperature difference between day and night is small, which creates ideal weather conditions for textile production.

Yuki sarashi (snow bleaching)

Yuki-sarashi (snow bleaching) is the process of spreading the woven cloth out on the snowfield and exposing it to the sun. It is an essential part of the process of making Echigo jofu, and the sight of the cloth exposed to the pure white snow is unique to YUKIGUNI (snow country).

Yuki-sarashi takes place in mid-February and late March, when there are many sunny days. Snow bleaching is said to have the effect of removing dirt. This is due to the fact that when the snow melts, ozone is produced, which bleaches the vegetable fibres. The number of days it takes depends on the type of fabric and the stain, but usually it takes about a week.

Tokamachi gasuri

After climbing a set of steep and narrow stairs, we come across wooden instruments used in fabric production, lined up in an orderly fashion, inside the workshop on the second floor. Among these instruments, the “seikeiki” (warping machine) which arranges the vertical threads in order, moves like a living thing when Mr Watanabe operates it.

Watakichi Orimono is one of now very few fabric workshops which have kept the production method of Tokamachi-gasuri alive. “My grandfather, who was purchasing silkworms in summer, started this as a work he could do during the winter months.” Very fine threads slip across Mr Watanabe’s hands and are arranged into vertical threads for weaving.

“You cannot produce these fabrics in dry areas. If it gets dry, there is static and the threads snap. We have the humidity of our snowy winters, but also, Tokamachi is located in a basin, and so the humidity of summer is stored in the basin.”

Mr Watanabe tells us that all work processes are done by hand, and it can therefore take several months to produce a tenth of a hectare of fabric. “You cannot lose focus during any stage of the process. If you lose focus, the threads get tangled immediately”. He says he really feels his work is worth doing when the final result is exactly as he wanted it to be.

Angin: Jomon period clothing

Thousands of years later, the Jomon cloth has been handed down in Tsunan in YUKIGUNI. The cloth is called “Angin”. Traces of Angin cloth have been found on Jomon pot, so it is thought that the cloth has been made since the Jomon period.

Angin is a weave from this region which uses natural fibres such as ramie. The “Narangoshi-Association” is the only organisation which has reconstructed each stage of the process, from the cultivation of ramie, the twisting of the yarn, using the same tools as in the olden days, to the knitting of the final material.

Ms Michiko Yanagisawa is a member of “Narangoshi-Association”. Ms Yanagisawa says with a smile: “Although making Angin takes a terrible amount of work, it is also fun. In winter, when we meet in community centres to twist the yarn and to knit the Angin, our hands are busy but our mouths are not. It’s really fun to chat with everyone. We work while exchanging recipes for the homemade food people bring along.” Maybe women who lived during the Jomon period also knitted Angin during the busy winters while chatting to each other and waiting for spring.

If you are interested in trying your hand at Angin making in Tsunan Town, please contact us.

Ideal for cultivating ramie

YUKIGUNI is an ideal place for cultivating ramie, the raw material used for linen. Ramie prefers cold regions with a lot of rain, high humidity and not a lot of strong winds. Therefore, it has been present here since ancient times.

Tokamachi yuzen zome

Ms Mihoko Takanano, who is a young designer working at a fabrics company located in Tokamachi which produces kimonos using “atozome” techniques, explained yuzen and shibori (tye-dye) dyeing techniques to us.

“Shibori” is a method whereby the fabric is tied together and the fabric is given a pattern. As is traditional, the fabrics are put in wooden pails for the colouring. “For fabric-dyeing, there are two kinds of processes: “yuzen” and “shibori”. By layering both techniques, original kimonos are created.”

We asked Ms Takano about the relationship between kimonos and snow. “The water in this region is extremely soft because the snow slowly permeated the ground. This water is ideal for dyeing. We also use this water to bleach the kimonos we have finished dyeing.”

This region is famous in Japan for the tremendous snowfall it experiences. So is this not a disadvantage? “As opposed to in Kyoto, textile businesses in Tokamachi have not been split according to each work process; in many places, the entire production is carried out by one business. This is because transporting the products during the manufacturing processes is difficult in an area with so much snowfall. But thanks to this, the high quality of the final product has been preserved.”

Mr Takano says she would immediately recognise a kimono produced by her own workshop. She says that it is not just the techniques which are passed down through the generations, but also what it means to be an artisan.

Things to do

Discovering YUKIGUNI Tour

Embark on a 4-day exploration of YUKIGUNI, an undiscovered Japanese region. Begin in historic Shiozawa, renowned for its weaving heritage, breweries, and medieval townscape. Savor local cuisine at a refined ryokan or learn from culinary masters. Encounter breathtaking nature, world-class contemporary art, and unwind in carefully chosen TIMELESS YUKIGUNI luxury inns.