By Matt Klampert

The term YUKIGUNI means “Snow Country” in Japanese. This is more than just a description of how this area looks during the long winters around Niigata, Nagano, and Gunma. For the people living here, snow is central to our culture as well. Although many of the towns that make up the Snow Country Tourism Zone are considered small by the standards of Tokyo or Osaka, it is in fact exceedingly rare to find so many people living in a place with so much snow. Snow Country is located at 37 degrees north latitude, but it is a world apart from other cities at the same latitude such as Lisbon, Sicily, Athens, and San Francisco. In other words, both the climate and culture of YUKIGUNI is wholly unique.

Jomon and the beginnings of “Snow Country Culture”

When discussing how people co-exist with snow in Snow Country, we should begin with the first societies that lived here- indeed, the first societies that existed in all of Japan! The Jomon were not a singular nation, but a nomadic hunter-gatherer culture that lived all over the country beginning over ten thousand years ago. The Snow Country area in particular has so many Jomon ruins that it is sometimes called “Jomon Ginza.” These Jomon were especially active in the area surrounding the Shinano River for thousands of years, and were able to thrive without needing to cultivate rice or raise livestock, and instead fished in the rivers and foraged for edible plants and nuts. Even at this early point in history, the Jomon had a knack for being able to tell, for example, those mushrooms that were edible and which were poisonous. Their understanding of the natural world even allowed them to predict when the climate would change.

Though there are no more Jomon in YUKIGUNI, those who have lived here from then on have always had to contend with this same climate. These days, people are grateful for the powder snow which transforms our land into fantastic ski country, but the snow here wasn’t always looked upon so favorably.

A history of co-existing with a vast natural world

A part of our culture here is not only coexisting with harsh nature, but also the local wildlife. YUKIGUNI is the southernmost point in Japan where you can find Matagi. The Matagi are nomadic hunters who may have existed in Japan for as long as one thousand years! Approximately 400 years ago, some of them left their usual ranges to settle around Nagano Prefecture, including Akiyama-go and the village of Sakae. The Matagi spent the winters in Nagano hunting and trapping, most famously bears. Matagi were often called upon by locals when bears were spotted close to villages, and they would hunt them in groups. In Akiyama-go, the Matagi put down roots, and some Matagi even opened accommodation called minshuku. Click HERE for more information about minshuku in YUKIGUNI, including places where you can learn about Matagi- even from Matagi themselves!

The area where the Matagi live, known as Akiyama-go, is itself very interesting. There is a lot to see, like the picturesque Maekura Bridge and Jabuchi Waterfall, and it has become a great place for outdoor activities, from glamping to bathing at the open-air baths at Kiriake and Koakazawa. For those looking to experience the true remoteness of the YUKIGUNI countryside, Akiyama-go is a place where it sometimes seems like time has stood still. Click HERE for information about Akiyama-go and the greater Naeba Sanroku Geopark.

-1024x683.jpg)

Travel through the famous snow-covered forests of Snow Country

When it comes to the natural world of YUKIGUNI, even the trees themselves are unique. Most Japanese woods are filled with cedar trees, but here you can walk through rare beech forests. Beech trees, like those at Bijinbayashi in Tokamachi City or along Yuzawa’s 100 Kannon Trail, are the representative trees of Snow Country, and are known for being able to survive in harsh climates. In particular, beech trees bend and twist under the weight of heavy snow, and their branches block out sunlight and keep the forests cool in summer.

Of course, now people from all over the world love to see our forests when they are the most beautiful: covered in pristine snow. In the past, prior to the start of mass transportation in Japan, people braved the snow using snowshoes called kanjiki to get from town to town. It is now possible to experience this yourself by joining one of our snowshoe tours! For info about snowshoe tours in this area click HERE. Snowshoe tours in Yuzawa’s Mt. Akiba and Daigenta Canyon are run by the Snow Country Tourism Association, a one-stop shop for all of your local tourism needs.

Growing under the snow: The food culture of YUKIGUNI

Just as important as the snow is what grows underneath. When people think about eating in Japan these days, they may think about mouthwatering ramen or gyudon, but the food culture in this region is a good deal older and largely plant based. Like the Jomon before us, we still forage in the mountains for delicious mushrooms and mountain vegetables called sansai. We also grow everything from asparagus to sweet corn. Our carrots, called “yukishita ninjin” in Japanese, are famous for growing underneath the snow. Not only do they not freeze, but are kept safe from insects, and the snow causes a chemical reaction that causes starches to turn into sugar and amino acids, making these carrots noticeably sweeter.

Though the locals of YUKIGUNI are blessed with being able to eat such fresh produce and delicious koshi-hikari rice for three meals a day, visitors can also experience our local cuisine at some of our prestigious farm to table eateries. Restaurants like Irori Jinen serve their homemade mountain-fresh cuisine in the traditional fashion, and there are even Michelin starred restaurants here, such as the restaurant at Satoyama Jujo, that utilize sansai and other ingredients in new and innovative ways. If you like, you can even try your hand at picking sansai yourself during the green season. Click HERE for more information.

Food preservation in snowy winter

But of course, people had to eat during wintertime too! Everything that was picked and remained had to be preserved. Common preservation methods include pickling with salt and storing in a yukimuro, a sort of “snow refrigerator.” Even these days you can find rows of houses making daikon tsugura – lean-tos made of straw- to preserve daikon radishes, or hanging persimmons outside their homes to dry. We now have a whole article dedicated to our unique methods of food preservation, check it out HERE!

Despite modern refrigeration techniques, one contemporary usage of yukimuro is for storing sake! Besides just being eco-friendly, the low temperatures and humidity of the snow aid the koji mold in the sake, which is a big reason for the great taste of the final product. Of the many sake breweries all over Japan, the superior quality of our water, which begins as snow, is one reason for the particularly great sake that can be found here. Click HERE to learn about some great local brands.

The craftsmanship of snow country

Traditionally, the people of YUKIGUNI made their living as farmers. But what can you do throughout the winter when snowed in? You will often find, in many of the old-style kominka farmhouses here, a place in the attic where people raised silkworms, and in the winter it was woven into special cloth called “Echigo Jofu.” Echigo Jofu was so important here because this was the primary method of earning money for many families during the winter. Due to its high quality, Echigo Jofu was sought out as far as Edo (present day Tokyo), where they were given as gifts to royalty and aristocrats, and kimonos made with Echigo Jofu still fetch a high price. Click HERE to learn how to sign up for your own kimono fitting in Snow Country.

The traditional wooden homes of Snow Country have also come to be appreciated for their ingenuity and craftsmanship. A hallmark of these homes were their raised floors and irori, or fire pit, where families gathered, ate, and kept warm during winter. Some of these kominka houses have been repurposed into unique accommodation, or even made into spectacular works of art courtesy of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale.

Celebrating the snow in the snow

One way to really feel the culture of any particular place is to join in yourself! The winter festivals of Snow Country have a long history, and are quite unique among Japanese matsuri- to the extent that some are known as Echigo Kisai, or “strange festivals” of Echigo. If you have ever wanted to be thrown down a snowy hill, see giant snow sculptures, or join a special “naked festival,” then click HERE to see more information about each one.

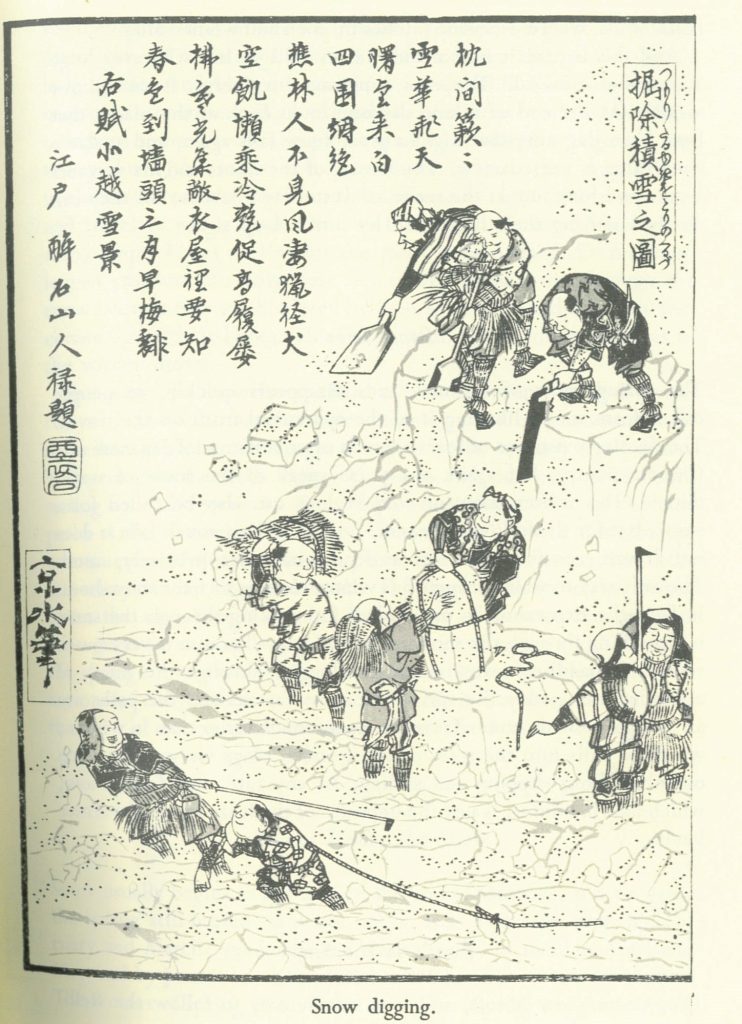

Learn about Bokushi Suzuki, the foremost chronicler of Snow Country’s unique culture

The idea of “Snow Country” was popularized and romanticized by the Nobel prize-winning author Yasunari Kawabata, but Kawabata himself was not from this area, and there was much about it that he didn’t know. To learn more about Snow Country, Kawabata read the works of another writer, a man named Bokushi Suzuki, whose influence in Snow Country can still be felt today. Bokushi published a collection of stories called Hokuetsu Seppu, or “Snow Country Tales,” which caused a sensation upon being released in 1837, and is still read today.

In order to learn all about the world of “Snow Country Tales,” why not visit Bokushi Suzuki’s own museum? Located in his hometown of Shiozawa in Minamiuonuma, the Suzuki Bokushi Memorial Museum contains many artifacts from Bokushi’s personal collection, both as a literary figure and in his capacity as a cloth merchant. As Bokushi was fastidious about keeping everything, there are all sorts of one-of-a-kind items on display, which include explanations in English. Also nearby is Bokushi-dori, the historic street that was renovated in an Edo-period style. It is the best way to experience the world as Bokushi knew it two hundred years ago.

Ensuring the future of Snow Country

It is our goal here to make sure that our culture isn’t just a thing of the past, but something that can continue on for another 100 years, or longer! For this reason, the way we see tourism has evolved, such as transforming our ryokan into sustainable eco-lodges. Click HERE to read more about them, and find one that is right for you!

More broadly, we also aim to continue to live in harmony with nature, and foster appreciation for it throughout the year. In YUKIGUNI there are over 300 km of hiking trails- from mountain passes to old thoroughfares that frequently pass by hot springs, shrines, and more. The local organization Snow Country Trails have been collaborating with locals to promote these trails, and now seek to open them up to travelers. Come join us, and learn about Snow Country culture for yourself!

Information for Travelers

Najomon Museum

Address: 835 Shimofunatootsu, Tsunan Town, Nakauonuma District, Niigata Prefecture 949-8201

Hours: Open 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., closed Mondays

Deguchiya

Address: 18174-2 Sakai, Sakae Village, Shimominochi District, Nagano Prefecture 949-8321

Phone: 025-767-2146

Open Year-Round

Bjijinbayashi Forest

Address: 1225-1 Matsunoyama matsuguchi, Tokamachi City, Niigata Prefecture 942-1411

Cost: Free to enter, separate fee required for tours

Access: Accessible by car all year round. Bus available during the green season from Tokamachi and Matsudai stations (Hokuhoku Line). When arriving at Bijinbayashi by bus, get off at the “Sakaimatsu” stop. Follow the signs to Bijinbayashi, which is an approximately 20 minute walk away.

Irori Jinen

Address: 718 Kamioritate, Uonuma City, Niigata Prefecture 946-0087

Hours: 11:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. or until sold out, closed Thursdays, closed from late November to mid-April

Hakkaisan Uonuma no Sato

Address: Nagamori, Minamiuonuma City, Niigata Prefecture 949-7112

For tour information, please inquire at the front counter on the day of your trip or call 0800-800-3865

Shedding House

Address: 776 Toge, Tokamachi City, Niigata Prefecture 942-1351

Suzuki Bokushi Memorial Museum

Address: 1112-2 Shiozawa, Minamiuonuma City, Niigata Prefecture 949-6408

Hours: 9:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.

Cost: 500 yen per adult